Making Peace

Research Trips to Slovenia

In 2022-24, I made three trips to Slovenia to

research the WW2 history

that forms the basis of my (still unpublished) novel, Making Peace.

Here's the Cliff's Notes version of the true story: In 1943 my great aunt Anne Dyck Kessenich (1926-2023) escaped Stalin’s Ukraine with the help of the retreating German army. Her family had lived in a German Mennonite enclave in eastern Ukraine for generations, but after the Bolshevik Revolution, they were targeted by harsh Communist policies. Then, when the Germans invaded in 1941, they lost most of their men to forced mobilization on the Eastern Front. Now, with the Red Army just a few miles from their door, the Wehrmacht offered their whole colony – all who were still alive – safe passage out of Ukraine. Anni was sent to a village in northern Yugoslavia (Podčetrtek, Slovenia), where she lived in a castle with other refugee women and taught in a local Kindergarten. As an ethnic German, she enjoyed protected status—until May 1945, when the war’s end brought not democracy to Yugoslavia but Communist rule. With thousands of others, Anni fled north to Austria’s British zone to avoid capture by the Yugoslav Partisans, Communists bent on revenge against any perceived enemies of the state. Instead of safety in the hands of the British, Anni and thousands of others were captured by Partisans. On a brutal forced march that culminated in the massacre of tens of thousands of surrendering soldiers and hapless refugees alike, Anni was shot in both legs and left for dead. Yet she lived to tell her story.

My aunt’s wartime experiences sounded like the stuff of a novel - part survival story, part coming-of-age.

I heard fragments of my Aunt Anne’s wartime experiences as a child, and felt the six bullet wounds on her shins that she carried into old age. It sounded to me like the stuff of a gripping novel—part survival story, part coming-of-age. Four years ago I began researching the historical background, beginning with a first-person narrative based on my sister’s extensive interviews with Aunt Anne twenty years earlier. I read both scholarly books and memoirs that shed light on Yugoslavia’s fraught history, its complex partitioning under occupying Axis powers, and the ferocious civil war that raged throughout and alongside World War 2 (which would give rise to the bloody wars of the 1990s).

Writing historical fiction requires a tremendous breadth of knowledge. I soon realized that while books were indispensable for understanding high-level battles, alliances, and treaties, they could not convey the taste of the local liquor, or the scent of native plants. So over a three-year period I made three research trips to Slovenia, each time interviewing historians, visiting sites that played a role in my aunt’s story, and imbibing the stunning landscape that would form the backdrop of my novel.

Below are photos from my trips which give just a glimpse of the complicated, compelling (and frankly still contested) history of Yugoslavia’s involvement in World War 2.

PODČETRTEK

CASTLE

A 13th-century castle in southeast Slovenia, 5 km from the Croatian border, became home to refugee women, including my Aunt Anne, in 1944-45.

BLEIBURG

& VIKTRING

FIELDS

Two fields in Carinthia, on the Slovenian-Austrian border, became synonymous with the post-war British betrayal and Partisan slaughter in May 1945.

...with the Karawank Mountains to the south.

...with the Karawank Mountains to the south.

PARTISAN INSTALLATIONS, KOČEVSKI ROG

Tito's Partisans were the most successful Resistance force in Occupied Europe, known for their tenacity and resourcefulness. Their hospitals and operational bases were cleverly hidden in wooded areas, concealed from aerial view.

REPRISAL KILLINGS AND MASS GRAVES

Post-WW2, the victorious Yugoslav Partisans turned on all perceived enemies of the state - surrendering Axis soldiers and hapless refugees alike. Hundreds of mass graves dot the Slovenian countryside, many of them still not exhumed.

An abandoned mining shaft-turned mass grave in 1945.

An abandoned mining shaft-turned mass grave in 1945.

Mihela's great aunt lived in Podčetrtek during the German occupation.

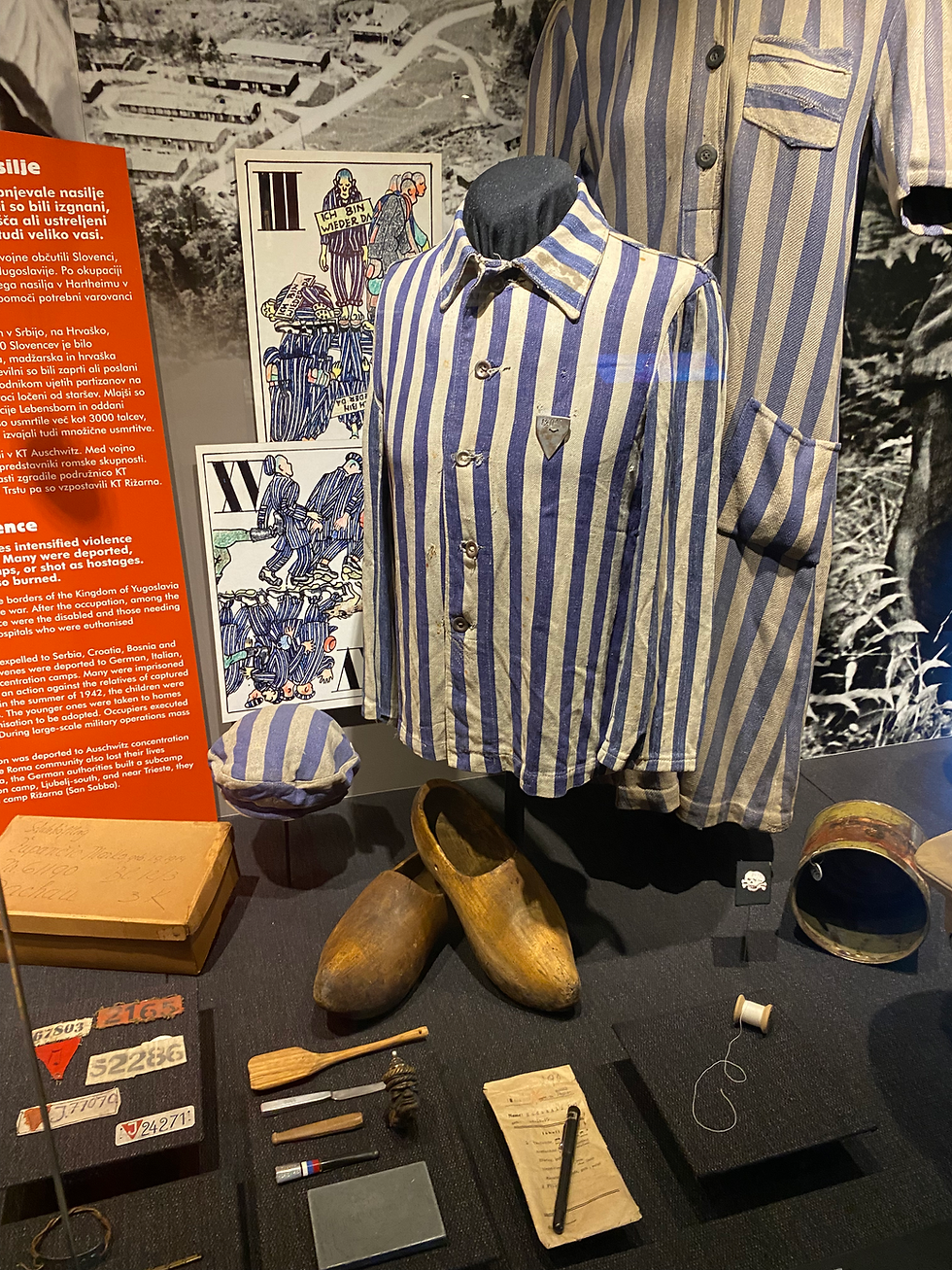

From the National Museum for Contemporary History, Ljubljana

Mihela's great aunt lived in Podčetrtek during the German occupation.

LIVING HISTORY

Interviews with historians and living witnesses, museum tours and historical site visits - all deepened my understanding of WW2 and the post-war conflict, and sparked my imagination for a fictional portrayal.

HOW TO STAY SANE WHEN YOU'RE RESEARCHING A WAR AND A MASSACRE

Slovenia has it all...mountains, lakes, beaches, wine country, cobbled cities, fabulous food, friendly people...all within a three-hour drive. My idea of paradise!